I had planned on posting this one today anyway, but after what I saw on Facebook this morning, I realise it's urgent.

My topic of the week is about how we think, how it affects us, and how much control we actually have over it all. You cannot have failed to notice that some people have opinions that make no sense. It's all very well saying that everyone is entitled to their opinion, but sometimes these opinions are based on misinformation, in one way or another.

Obviously this takes many forms, but the ones we see most are beliefs formed in childhood, usually from parental teaching, or in a broader form from the surrounding culture. This is going to include religious beliefs, but importantly they may not be orthodox. Think of the pentecostal snake handler families, for example.

But they may just as easily be political beliefs, which children are perfectly capable of taking on board as "facts" if they are presented in such a way. We see this quite often in the middle east, and 3 generations of Turks have a flawed knowledge of their own history. In some places parents actively discourage children from learning a second language which could in fact offer more opportunities for them later in life, for political reasons.

Then, of course, there are prejudices and biases; racism and sexism of all types could be mostly eradicated if it was never learned young. Remember the song:

And let's not forget general misinformation such as creationism, which while it may or may not have an element of religion, goes against current scientific thinking. So there are plenty of other examples here, mostly passed on by parents who simply don't know any better, but all too often deliberately.

Finally there is the absence of critical thinking itself. Believe it or not, many parents and certain types of teacher do not want children to learn critical thinking skills, because they may question the beliefs of their culture. But in any case, without those skills, kids grow up into adults unable to discern from the information presented to them. They fall for tricksters. They go on doing it, because they mix with others caught by the same tricks, and they reinforce one another's beliefs.

And so it has been with a heavy heart that I have read all the conspiracy theories surrounding the disappearance of the Malaysian plane.

Yes, it's amazing, isn't it, that something that big could disappear without trace, and I don't think there's any question that foul play could have been involved. But, just as easily, there could be a perfectly innocent explanation.

I'd like, therefore, to draw your attention to this article, which in itself is a classic piece of conspiracy theory, but, as always, it's the comments that are even more interesting.

http://www.naturalnews.com/044430_Malaysia_Airlines_official_story_government_cover-up.html

You will find an awful lot of insulting going on there, so I'll group them for you. They fall under:

A) You are stupid if you believe this.

B) You are stupid if you don't believe this.

C) You are stuipid for making your particular comment.

D) You are stupid for calling that particular comment stupid.

And then, like a breath of fresh air, there are commenters like Kyle, who begins with "This is a ludicrous story " and offers a simple, rational possible explanation. Occam would be proud. He also explains just how and why misinformation spreads, and this is the crux of the problem.

But what happens next in any situation like this is very interesting.

While people have all sorts of ideas about what happened in any strange event, you can group people broadly into believers and skeptics.

This is not good vs. bad, because it can go both ways, it's more to do with how people choose what they read and how they read it.

There are those who call themselves skeptics, for example, because they honestly think that by doubting every news report and governmemt statement they are automatically closer to the truth. The statement that inspired me to add this section about the plane said (of this article):

" I don't trust any government...this story is much more believable than what the Malaysia government is saying!

Scary!!!"

She thinks that because she's skeptical of official reports, that makes her wiser. She does. That's her angle.

On the other hand, she is willing to believe an article written by a complete stranger, on a website that is famous for conspiracy theories. She probably doesn't know that, the point is, she probably doesn't care/hasn't checked.

Skepticism is not, actually, disbelieving official statements. It is questioning ALL statements. The true skeptic would not automatically accept the unofficial version anymore than it would the official one.

Let's leave the plane and look at skepticism a bit closer.

You commonly see skepticism in religious matters. The same applies here, however. The skeptic is not not necessarily saying "That isn't true". He's saying "How do we know this is true? It may or may not be. Let's examine it a bit closer". He asks why. He considers possibilities. He is not a believer, obviously, but he's not dismissing the beliefs either.

It is possible that aftrer due consideration, he will become a believer. But it's much harder for the opposite to happen. Someone who is a believer tends to stay that way.

I could easily write an entire post on skepticism with regard to religion, or indeed to politics (which I'll return to), but I find it just as interesting to see how it plays out in more ordinary ways.

A good example is the microwave article I posted yesterday. One of my friends commented, including the following:

" I have a friend who recently got rid of her microwave because someone told her it was "dangerous" and now she reheats leftovers on the stovetop."

We don't know who that "someone" was but I would bet good money that it wasn't a scientist. I'd throw a few more bucks on the pile, that if I said this to her she'd tell me "Well, you can't trust scientists" which I've heard many times. They are, appararently all scoundrels hellbent on killing us off with their new-fangled ideas. In league with governments, no doubt.

So, here we have those who are quick to be skeptical about science, but happy to believe "someone".

I've lost count of the times I've seen examples of this.

Before anyone objects, no, scientists and doctors and governments and engineers and whatever other experts don't always get it right. We know that. But they don't always get it wrong, either. And they have at their disposal the best information available.

There are, without doubt, corrupt governments who deliberately feed misinformation to their citizens. The Ugandan government has been telling its people for years that HIV does not cause AIDS, thus excerbating the problem and preventing treatment being available to sufferers. The Ugandan government is one of the most corrupt governments in the world, possibly second only to the North Korean. And ducks tend to quack.

But it doesn't mean they are all at it.

Governments do tell lies. Yes, they do. Trusting them implicitly would be a mistake. Assuming every damn thing they do or say is a cover up or evil plot to kill us all is also a mistake.

Ah, you say, how do we know who or what to believe? It's getting SO HARD!

Actually, it's never been easier.

200 years ago your government could have told you any old bollocks it felt like and you'd have been none the wiser. Actually, they did tell you a load of old bollocks. They told you that black people were lesser than white people, that they couldn't be allowed to be free, because civiliation would collapse. A bit more recently they told you women couldn't vote because they were lesser than men, and if they got into politics civilization would collapse. I'm sure you can think of more examples.

Today with the collected wisdom and knowledge we have access to around the world it's very hard to fool the masses. You might get away with it for a short time, but it won't last. There are far too many skeptics hanging on your every word and checking it out.

AHA! cry the conspiracy theorists, that's what we're here for.

Except, the vast majority of them argue just as aggressively among themselves, if not more so, than any arguments they have with normal people.

Few of them are skeptics at all. The vast majority are simply hangers on who have chosen to believe charismatic mouthpieces rather than mainstream spokespeople.

It gets harder when the "alternative" version of events is credible. It's not all tinfoil hat stuff.

So we can divide it all into two groups. That which can be easily disproven by High School level science, and that which requires real expertise.

A term goes around in these discussions, and it's pseudo-science. It's used quite fairly in some cases, perhaps less so in others, but the problem seems to be that many of the "alternative" people don't actually know what science is. This leads them to using the word wrongly, and making silly statements like "Well, science doesn't know everything!" (Statements that begin with "Well" can be read as "My uneducated opinion is....")

Nobody knows everything. There is always room for more information, and it's certainly true that there are people on the science "side" who are arrogant, dismissive, and therefore careless in their assumptions.

A good example of this is the vaccination debate, which I usually stay out of, and the reason is exactly examples like this. In a recent heated debate (oh boy, and how) about how those who chose not to vaccinate their kids are going to kill us all (hyperbole is not limited to "alternative" views). During the argument (can't call it anything else) one poster said:

"Vaccines never harmed anyone!"

I could feel a lot of wincing but nobody challenged it, proving that outrageous remarks and unreasonable peer support can occur anywhere.

It is statements like "always" and "never" and other generalisations that cause so much of the problem. And these are statements made by believers, not skeptics. A believer has stopped asking questions, stopped looking for exceptions, stopped examining other possibilities. He knows. He's right.

In so many spheres, and so many examples, those who think they are skeptics are just believers in the opposing view. Nothing more or less. They have chosen a side. It may be the right side, that doesn't matter. The believer is set is his belief.

A true skeptic may arrive at the same conclusion, but not by knee-jerk assumptions. Not by reading only one side of it.

So, if you want to ask me when governments are dangerous, I shall tell you. It is when those within the government are believers.

In Britain over the last few years a terrible injustice has happened. It could happen anywhere, and this type of injustice does indeed occur all over the world, and in many ways, but this one has affected people I know, so I took a particular interest in it.

Britain, as you probably know, has a well-established benefit (welfare) system, that theoretically acts as a safety net for all its citizens. In theory British citizens will be taken care of by their government if they are unable to care for themselves. In practice this is a terrible financial strain on the national budget and not surprisingly steps have been taken to see if some money can be saved.

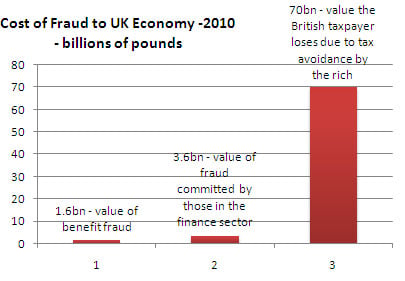

Somewhere along the way the idea was put forward that benefit fraud was costing the country over a billion pounds a year. So measures were taken to clamp down on this, and many genuine people lost income as a result. Newspapers were full of stories of hardships and even suicides. But the taxpayer stood firm. These cheats were getting what they deserved. People were encouraged to rat on their neighbours.

And they believed this. The government and the taxpayer were united in the belief that this was the problem, and OK, it was sad if a few kids went hungry, but something has to be done. And this is what has to be done. So they did it.

Except the bare facts are that tax fraud costs the country many times that.

This is data. Hard numbers. The government isn't even disputing them. But beliefs won the day.

Nobody is saying that benefit fraud is OK, it isn't and yes, some money has to be spent to stop it. You have to buy an alarm to stop a robbery. There's no question there. But when cause and effect is this skewed there's a problem.

There just isn't enough skepticism around.

In the case of the jet, I think so many people forget how really big the Earth is. Also I have a huge problem with "journalism" today using what amounts to personal blogs as news. That problem is one that extends from a local newspaper all the way to many national news sites. People write about what they believe and it gets published as news. I wish my journalism teacher was around to put them in their place.

ReplyDeleteI tend to be a skeptic even in places where scientists are involved. It bothers me that in some studies certain vitamins are found to help and another study comes out saying they don't. So I tend to have to find out for myself. I want to know everything and I want to know that what I know is really the correct answer. Which makes life frustrating.

It's never bad to be a true skeptic, the best scientists are true skeptics, that's how they discover new things, they don't accept that there isn't another way. So, when studies contradict each other, these are the people who try again, and try to see what they did wrong to get contradictory results before. They ask and they ask and they ask.

DeleteAnd I absolutely agree on the journalism.

"These cheats were getting what they deserved. People were encouraged to rat on their neighbours."

ReplyDeleteI had been reading a lot from a person who lives in England and receives benefits because her son is disabled. It is shocking. I like to read the articles that she posts because I feel it gives me a new perspective. I found this so tragic.

I live in Chicago and there is a ton of welfare fraud. It is so systemic that if they tried to have people turn in their neighbors--EVERYONE that could would. It's a mess.

Really, I feel you may be dealing with more than just the either/or of believe and skepticism. That may be the bottom line dichotomy, but the overall arch is the control of information; possibly the energetic use of information to sway public opinion.

ReplyDeleteOf the two choices, I tend to lean more toward skepticism, which means that any truths I may believe can and do change. Beliefs have changed, over time, with maturity and additional information. We have such trouble accepting this, and I don't know why. I would much rather explore possibilities than be tied down to a particular belief that limits just about everything else.

Getting back to the control thing, I find looking at basic elements is particularly enlightening. We may consider that we are comprised of a lot of water. Water, itself, may be considered an inert substance (as many of us may be apathetic and unmoving). Apply a tidal force, maybe a bit of gravity to it and it will move, however we may channel it. Take some other extreme influence, such as heat (which will get it boiling or steaming) or cold (which will freeze it into place even more solidly), and maybe we can see from another dimension where "all this noise" (and words are vibration) leads us. Any determination as to 'who' or 'why' may be a matter of semantics...maybe we're all in it for the 'challenge?'

There is some choice in the matter, but the fact is these stories (call them by whatever label suits--religion, conspiracy, psy/ops), are more about external control (more so than choice). Scientific data, biblical/archaeological proof, even sensory input (special effects, anyone?) can be MANipulated, and are limited not only to our direct experience, but what "others" can get in. ~ Blessings! :)